In May 1936, Consumers Union Reports published its first issue. It included articles on milk, breakfast cereals, soap and stockings, ranking each of them Grade A and Grade B. Another article argued that credit unions are better than banks, while yet another analyzed Alka-Seltzer and criticized its effectiveness, stating that its claims “vanish like the gas bubbles in the air.”

Consumer Reports was revolutionary. (The name of the magazine was changed in 1942 to make it accessible to all readers, not just union members.) And it was criticized by other publications. Reader’s Digest attacked the publication in 1939, and Good Housekeeping, whose Seal of Approval had been called a fraud by the Consumers Union, accused Consumer Reports of prolonging the Depression.

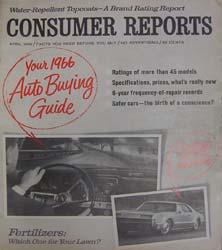

Never before had journalists joined with researchers to assess the quality and efficacy of products being purchased by millions of consumers. The publication was immediately successful. By 1940, it started asking readers questions about products, and by 1946, circulation had reached 100,000. Subscriptions reached 400,000 just four years later, and in 1952, the magazine published its first frequency-of-repair table for automobiles.

What Consumer Reports did that no other publication had ever attempted was to have products tested by scientists before they were included in an article. In addition, the results of similar products, through scientific tests, were compared to each other, allowing readers to determine which product was more suited for their needs. The magazine became known for its aggressive coverage of products and wasn’t afraid to criticize companies.

For example, a 1942 article showed that the differences in tar and nicotine were insignificant when it came to the harmfulness of smoking, fully a decade before additional concerns about smoking cigarettes were published. As a result of the article, cigarette maker Lorillard launched a national campaign taking advantage of the article, which showed that one of its brands was “lowest in nicotine and tars.” The Federal Trade Commission ordered a cease-and-desist order for the ad campaign, noting that its ads were false and misleading because it only printed a small part of the Consumer Reports article.